By Oseloka H. Obaze

Democratic consolidation requires holding periodic elections that allow for a peaceful transfer of power. Yet some elections held outside of consolidated democracies have been identified as sources of conflict. So far, Nigeria has managed to skirt around its various electoral crises, thus avoiding ensuing conflicts. But all is still not well. As long as the outcome of Nigeria’s 2023 presidential elections remains under contestation, a conjunction of circumstances will determine Nigeria’s political trajectory, more so as her national resignation and seemingly unfettered elasticity in tethering on the precipice, may have reached the breakpoint.

The foundational and sustaining basis of any democracy is the holding of periodic and genuine elections that allow a nation’s citizen to exercise their universal suffrage. The one-man-one-vote practice is one of the affirming principles of equality of persons, regardless of social and economic stratification. However, when a nation is leadership challenged as Nigeria is present, it becomes incumbent for certain individuals and national institutions to rise to the occasion and toe a remedial path.

It is no longer in question that the quest for good governance and purposeful leadership is contingent on holding credible elections. Relatedly, the path to national greatness requires courage and selfless sacrifice. Both traits seem to have eluded Nigerians. There is, indeed, a dearth of both in our nation-building matters. This reality has placed Nigeria in its present conundrum. As much as some may indulge in escapism and declare the 2023 presidential elections concluded, that is not the case. The matter and the fate of Nigeria now rest with the Nigerian judiciary.

The present state of play affirms the truism espoused by Justice Mosunmola Dipeolu, that “It is essential for good governance to have a formidable judiciary. It ultimately contributes to nation-building, because it stands as the watchdog of the society and does not allow the hope of common men to be lost.” The moment of truth is here!

For now, Nigeria’s 2023 presidential election results remain in dispute. Those who urge the acceptance and grandfathering of INEC’s egregious declaration neither have an eye on history nor are interested in Nigeria’s long-term well-being. Expediency in such national interest issues will always be fraught with miasma. No nation should legislate or legally sanction criminality. What Nigerians ought to be doing to escape the present quagmire is delving into its history and looking elsewhere for guidance, if need be. There are for Nigeria, some close-to-home examples.

In 2017, the Kenyan Supreme Court declared the presidential elections held on August 8 as “null and avoid,” citing grave irregularities. As the Court ruled, “The presidential election held on August 8 was not conducted in accordance with the constitution.” The court then ordered a new poll to be conducted within 60 days. It was a landmark decision.

Similarly, in 2020, the Malawi Supreme Court upheld a Constitutional Court ruling that President Peter Mutharika’s 2019 election was invalid because of widespread irregularities. In annulling the elections seven months later, the court cited “widespread, systematic and grave” irregularities including significant use of correction fluid to alter the outcome. Consequently, it declared, “We consider that” Peter Mutharika “was not duly elected on 21 May 2019. We, therefore, annul the results of the presidential election.” The Court went on to order a new presidential election to be held within 150 days. For Malawi, democracy and history, it was a landmark decision.

The rulings by the Kenya and Malawi apex courts present seminal case studies in politics, history, and jurisprudence. Contextually, two unique strands should always guide public policy decision-making: lessons learned and missed opportunities. These are tantamount to the use of history, precedent, or experience for decision-making. Put differently, precedents in law, convention, or practice are valuable instruments of leadership decision-making processes. In Nigeria, the landmark case, Awolowo vs. Shagari has been characterized by some as a case of compromise; the truth remains that the Supreme Court if it had any bias, was in favour of upholding tenets of the Constitution.

Before Malawi’s election, the international community, including the United Nations, European Union, and African Union, issued several statements ahead of the vote, by which they urged Malawians to uphold the rule of law and remain calm. In the aftermath of the elections, when there was clear consternation and discomfiture over the announced results, the same international bodies sued for calm, reminding the nation that “Malawi can draw on an impressive history of institutions and leaders stepping forward to safeguard your democracy and ensure peaceful resolution for internal tensions.” These exhortations have been and can be easily replicated in the circumstances presently confronting Nigeria.

What is left is for the Nigerian judiciary to find the courage and need for self-sacrifice against all odds, to affirm the supremacy of the Constitution and the eminence of the rule of law. Both acts are synonymous with Patriotism. Given Nigeria’s peculiarities, such hard-headed decisions are not for the faint-hearted. But nations have been rescued from perdition via such conduct.

Like equity, jurisprudence has universal value. Transformative legal rulings are transboundary. Precedents arise and are employed by every legitimate authority. This is more so in our globalized world and with the benefit of seamless information technology. Whereas some have argued that it’s folly to mistake precedent of court cases for knowledge and that any such endeavour is not by itself law; it goes without saying that precedent is the GPS of law and an indisputable guide on extant principles.

There are unambiguous parallels in the Malawi and Nigeria presidential election cases. In Malawi, one of the grounds for annulling the elections was “irregularities, especially ‘massive’ use of correction fluid on results sheets.” In Nigeria, evidence abounds of result sheets that were “blurred,” “mutilated,” and carelessly altered, with the use of “correction fluid on result sheets”. Such evidence exists and is incontrovertible.

Everything that could possibly go wrong with an election went wrong with the 25 February presidential elections, thanks to INEC. Of the lot, the worst misdeed, which borders on criminality, is the egregious debasement of the Nigerian Constitution, thus creating a constitutional crisis. INEC also flunked the doctrine of substantial compliance. It put provisions of the Constitution in auto reverse, more so in neglecting dictates on winning requirements for Abuja FCT. Consequently, the judiciary negating this INEC legerdemain will not in spirit and letter amount to judicial legislation as some may presume.

Nigeria is like Kenya; like Malawi, no questions asked. Yet this needs to be asked: Can the Nigerian judiciary find the courage to uphold the constitution? As the song says, “The answer is blowing in the winds.” Whether it will be good winds or ill winds remains to be seen.

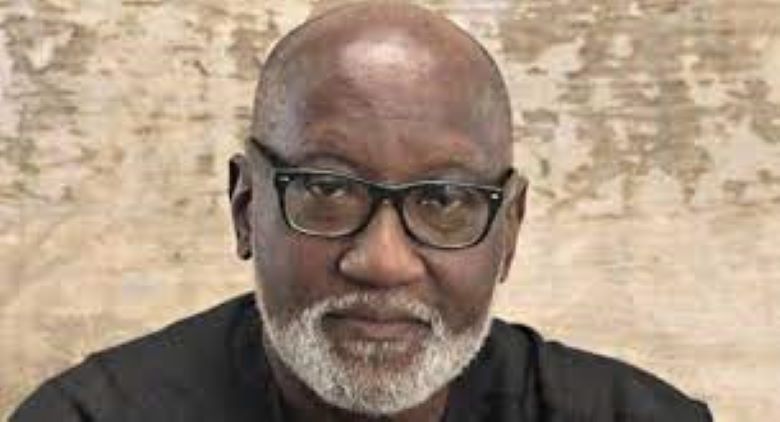

Obaze, a politician, diplomat, and governance and public policy expert, is a card-carrying member of the Labour Party.